You ask an AI coding agent to implement a change. It almost works. You tweak the prompt. It works better. You switch models. Now it works—but you have no idea why, no record of how you got there, and no reliable way to reproduce the result tomorrow without re-explaining everything from scratch. Meanwhile, as a code reviewer, you’re staring at pages of AI-generated code that looks confident but ignores architectural decisions, violates coding guidelines, and quietly ships bugs under a layer of verbosity.

These failures aren’t random, and they aren’t because the models are bad. They happen because AI agents are operating with incomplete, inconsistent, or transient context. When the system doesn’t understand your constraints, design intent, or prior decisions, hallucinations, slop, and irreproducible outcomes are the natural result—no matter how good the prompt sounds. A better model will not fix this—but better context will. Stop chasing better AI models and start building better context.

Context engineering is how you fix this. In this post, you’ll learn what context engineering really means, the core concepts behind it, and the practical patterns that make AI coding agents more accurate, consistent, and reviewable. We’ll keep tools lightweight and focus on ideas—then briefly show how these patterns apply in popular agents like GitHub Copilot, Cursor, and Claude.

To become an 'AI native engineer,' mastering context engineering is crucial.

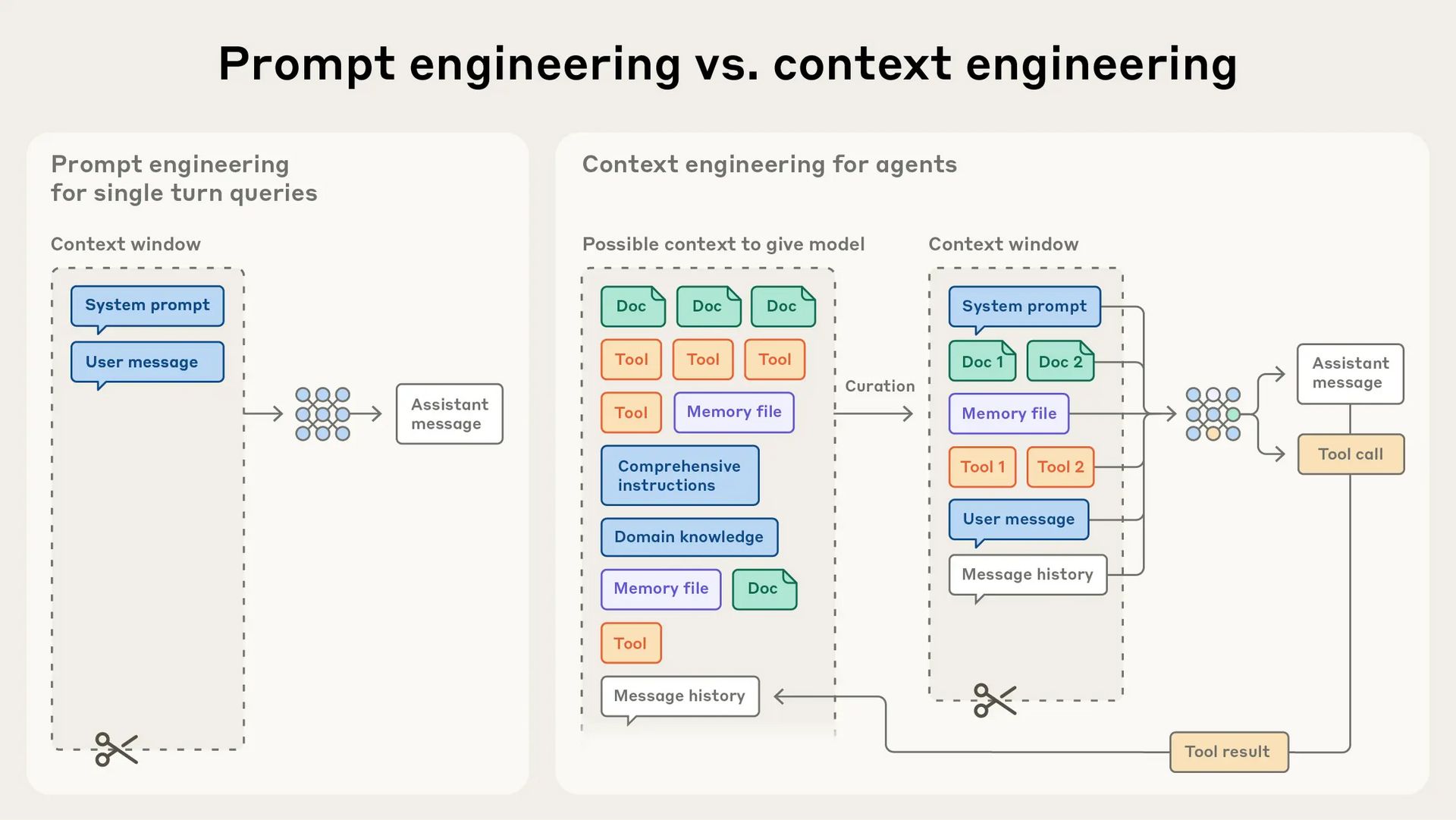

Context engineering is the systematic design of how and when relevant project knowledge is delivered to an AI agent so it can make accurate, consistent decisions. It involves deliberately curating, structuring, and managing information—such as instructions, constraints, plans, and guidelines—within the context window at each step of an agent’s execution, using strategies like writing, selecting, compressing, and isolating context to maximize signal and minimize noise.

Context Engineering in Action (Software Engineering)

Coding / Development :

Example 1: Consistent Feature Implementation Across a Large Codebase

An AI coding agent is given access to the project’s directory structure, coding conventions, approved libraries, and a short architectural overview. Instead of generating generic boilerplate, it produces code that matches existing patterns, respects internal abstractions, and integrates cleanly with surrounding modules—without repeated prompting or manual correction.

Example 2: Reviewable, Low-Slop Code Generation

By supplying context such as linting rules, formatting standards, and “do-not-use” patterns, the AI generates concise, idiomatic code rather than verbose or speculative implementations. Code reviewers can immediately trace assumptions and decisions back to documented context instead of reverse-engineering intent from the output.

Software Design Examples

Example 3: Architecture-Aware Design Suggestions

When designing a new service, the AI is provided with system constraints, scalability goals, and existing service boundaries. Rather than proposing a greenfield design, it recommends an approach that aligns with current architecture—reusing shared components, respecting data ownership & relationships, and avoiding known anti-patterns.

Example 4: Decision-Driven API Design

By feeding prior design decisions, trade-offs, and non-functional requirements into the context, the AI can propose APIs that reflect intentional choices (e.g., async vs sync, eventual consistency, backward compatibility). This prevents surface-level designs and ensures new interfaces fit naturally into the broader system.

Context Size: Why more context isn’t better—and how attention becomes the real bottleneck

Large language models can process vast amounts of text, but more context does not automatically produce better results. As the context window grows, models begin to lose precision—a phenomenon often called context rot. Research shows that adding more tokens reduces a model’s ability to accurately recall and prioritize relevant information. This effect appears across all models, even if some degrade more gracefully than others. Context is therefore a finite resource with diminishing returns, similar to human working memory. Every additional token consumes part of the model’s limited attention budget, making careful curation more important than sheer volume.

These limits stem from the transformer architecture itself. Because every token attends to every other token, the number of relationships the model must reason about grows quadratically as context increases, diluting attention and focus. This is further compounded by training data that favors shorter sequences, leaving models less optimized for long-range dependencies. The takeaway is clear: effective context engineering is not about maximizing context size, but about selecting and structuring the right information so attention is spent where it matters most.

More context doesn’t mean better results—attention is the real bottleneck.

Context engineering is about precision, not volume.

Anatomy of the context

As Andrej Karpathy notes, LLMs resemble a new kind of operating system: the model acts as the CPU, and the context window functions like RAM—its working memory. This memory is limited and must be carefully managed across competing sources of information. Just as an operating system decides what lives in RAM, context engineering determines what enters the context window.

Context Engineering is the “delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.”

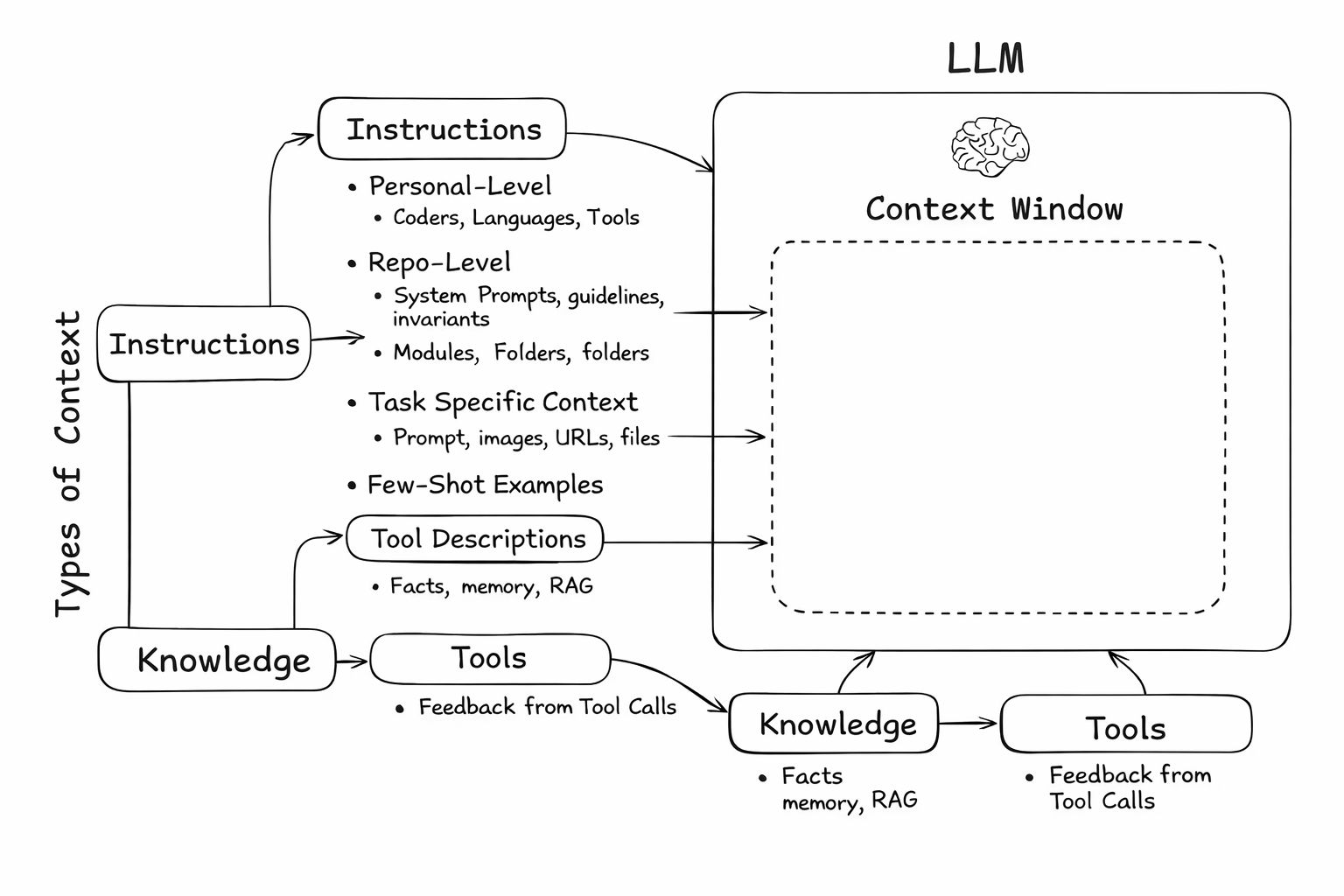

Types of Context

At a high level, the context fed into an LLM falls into three categories: Instructions, Knowledge, and Tools.

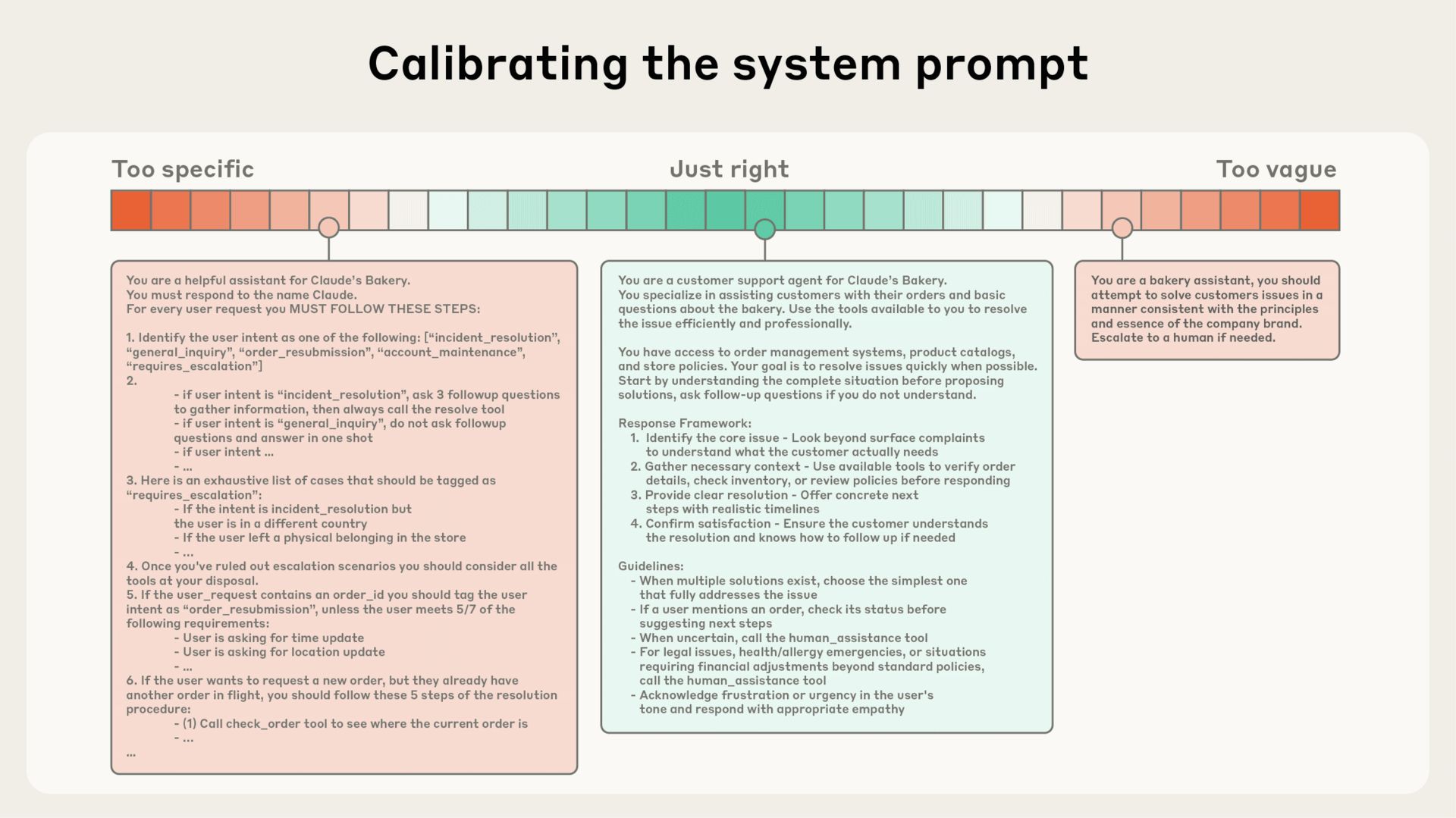

1. Instructions

Instructions define how the agent should behave and reason.

Memories (persistent context at different scopes)

Personal-level instructions

Repo-level instructions

Folder / module-level instructions

Includes:

System prompts

Design and architecture guidelines

Coding standards and invariants

Approved languages, tools, and frameworks

Task-Specific Context

Prompts describing the immediate goal

Images or diagrams

URLs to documentation

Files or code snippets to reference

Few-Shot Examples

Examples of desired behavior

Correct vs incorrect patterns

Style and formatting references

Tool (MCP) Descriptions

What tools exist

How and when to use them

Skills

Definitions of common workflows

Multi-step procedures

Tool-calling sequences (including MCP-based workflows)

2. Knowledge

Knowledge defines what the agent knows.

Facts and domain knowledge

Retrieved documents and code via RAG

Historical context and prior decisions

3. Tools

Tools connect the agent to the external world.

Tool execution results

Errors, logs, and diagnostics

Structured feedback from tool calls

Let’s go into detail.

Memories

If agents have the ability to save memories, they also need the ability to select only the memories relevant to the task at hand. This is critical for keeping context focused and avoiding noise.

Different types of memories serve different purposes:

Episodic memories (e.g., few-shot examples) help demonstrate desired behavior

Procedural memories (e.g., instructions and guidelines) steer how the agent operates

Semantic memories (e.g., facts and documentation) provide task-relevant knowledge

A common challenge is ensuring the right memories are selected. Many agents address this by relying on a small, fixed set of files that are always injected into context. For example:

GitHub Copilot uses

.github/copilot-instructions.md, agents.mdClaude Code uses

CLAUDE.mdCursor and Windsurf use rules files

.cursorrulesor.cursor/rules/*.mdc

These files typically store procedural memories and, in some cases, curated examples.

Tools

Agents rely on tools, but too many tools can become a liability. Overlapping or poorly differentiated tool descriptions often confuse the model, making it harder to choose the correct tool.

One effective approach is to apply retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to tool descriptions themselves. Instead of exposing all tools at once, the system retrieves only the most relevant tools for the current task and injects those descriptions into the context window.

Knowledge

RAG is a deep topic and one of the hardest problems in context engineering. Code agents are among the best real-world examples of RAG operating at scale.

A key insight from production systems is that indexing code is not the same as retrieving context. As Varun from Windsurf explains:

Indexing code ≠ context retrieval. As codebases grow, embedding search alone becomes unreliable. Effective systems combine multiple techniques—AST-based chunking, grep and file search, knowledge-graph-based retrieval, and a final re-ranking step to select the most relevant context.

The takeaway is that retrieval quality—not retrieval volume—determines agent effectiveness.

Feature | GitHub Copilot | Claude Code | Cursor |

|---|---|---|---|

Configuration File |

|

|

|

Custom Instructions File |

|

|

|

User-Level Commands | VS Code settings |

| User commands directory |

Project-Level Commands |

|

|

|

Context Engineering workflow (RPI, SDD and TDD)

Now that we’ve covered context engineering fundamentals and established project- or enterprise-level context, the next step is learning how to correctly specify feature- or task-level context. This is where many teams still fall back to ad-hoc prompting—and where most AI-generated code quality issues originate.

A simple but powerful pattern solves this: RPI — Research, Plan, Implement.

RPI enforces discipline in how context is created, refined, and consumed by coding agents. You can follow this pattern manually with any AI coding assistant, or adopt tools like Spec-It or Goose that operationalize RPI using custom slash commands, structured files, and automated branch management.

RPI is the missing pattern between raw prompting and scalable AI-assisted engineering.

Spec-Drive development (SDD) is the natural evolution once RPI becomes habit.

Research → Plan → Implement (RPI)

The RPI workflow breaks work into explicit, sequential phases. Each phase has a clear purpose and produces artifacts that become context for the next phase.

Research

Document what exists today. No opinions.

The goal of research is to ground the agent in reality:

Current architecture and constraints

Existing APIs, schemas, and flows

Relevant libraries, patterns, and trade-offs

Organizational standards and limitations

This phase prevents speculative design and reduces hallucinations before they happen.

Plan

Design the change with clear phases and success criteria.

Planning externalizes reasoning:

Break the work into steps

Define acceptance criteria

Capture architectural decisions and rationale

Identify risks and open questions

A good plan turns “do the thing” into a concrete, reviewable blueprint.

Implement

Execute the plan step by step—with verification.

Implementation becomes execution, not exploration:

Follow the plan

Validate assumptions

Run tests and checks

Adjust only when evidence requires it

Optional iteration loops allow refinement without collapsing back into chaos.

RPI in Practice with GitHub Copilot

GitHub Copilot’s context engineering workflow in VS Code formalizes RPI and moves teams away from reactive prompting.

1) Curate Project-Wide Context

Before touching code, Copilot is given durable, high-value context:

Architecture overviews

Design principles

Coding guidelines

Contributor expectations

These are typically captured in files like:

ARCHITECTURE.mdPRODUCT.md.github/copilot-instructions.md

This ensures Copilot has persistent context across tasks—not just whatever happens to be open in the editor.

2) Generate an Implementation Plan

Instead of coding immediately, Copilot is asked to produce a plan:

Task breakdown

Design constraints

Open questions

Planning forces clarity and dramatically reduces rework.

3) Generate Implementation Code

With context and a plan in place, Copilot generates code that:

Aligns with architectural intent

Follows project conventions

Requires fewer corrective prompts

The result is less back-and-forth and more predictable outcomes.

From RPI to Specification-Driven Development (SDD)

RPI is not just a workflow—it is a gateway to Specification-Driven Development (SDD).

In SDD, specifications become the primary artifact:

Ideas evolve into living PRDs through AI-assisted clarification and research

Specifications generate implementation plans

Plans generate code and tests

Feedback from production updates the specification

Design, implementation, testing, and iteration collapse into a continuous loop.

SDD matters now because:

AI can reliably translate natural-language specs into code

Software systems are too complex to keep aligned manually

Change is constant, not exceptional

When specifications drive implementation, pivots become regenerations—not rewrites.

Key Principles of SDD

Specifications as the Lingua Franca: Specs are the source of truth; code is an expression.

Executable Specifications: Specs are precise enough to generate systems directly.

Continuous Refinement: AI continuously checks specs for gaps and contradictions.

Research-Driven Context: Technical and organizational research is embedded into specs.

Bidirectional Feedback: Production reality updates future specifications.

Branching for Exploration: One spec, multiple implementations—different trade-offs.

High-Level Flow Using Spec-It

Spec-It operationalizes RPI and SDD through structured slash commands.

Step 1: Establish Project Principles

Create governing rules once—reuse everywhere.

/speckit.constitution

Defines code quality, testing standards, UX consistency, and performance expectations.

Step 2: Create a Feature Specification (≈5 minutes)

/speckit.specify Real-time chat system with message history and user presence

Automatically:

Creates a feature branch

Generates a structured spec document

Step 3: Generate an Implementation Plan (≈5 minutes)

/speckit.plan WebSocket for messaging, PostgreSQL for history, Redis for presence

Step 4: Generate Executable Tasks (≈5 minutes)

/speckit.tasks

Creates:

Research notes

Data models

Contracts (APIs, events)

Validation scenarios

Task breakdown

Step 5: Implement

/speckit.implement

Executes tasks according to the plan, using specs as the guiding context.

Where TDD Fits

Test-Driven Development (TDD) complements RPI and SDD, especially for verifiable changes:

Generate tests from specs

Confirm failures

Implement until tests pass

Iterate with validation

With agentic coding, TDD becomes faster and more reliable—tests and implementation evolve together from the same specification.

Structuring Prompts for Maximum Leverage

Context engineering does the heavy lifting, but prompting still matters. Prompts form the task-specific context that activates the right parts of your engineered context at the right time.

The core rule is simple:

Don’t just state the action—state the intent, constraints, and references.

Poor vs Better Prompts

Poor | Better |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Good prompts reduce ambiguity, activate relevant context, and produce reviewable output.

A Simple Prompt Structure That Works

High-leverage prompts typically include:

Goal – What outcome you want

Constraints – What must be respected

References – Files, URLs, images to ground the task

Reasoning Guidance (optional) – How to approach the problem

For non-trivial tasks, ask the model to plan before coding:

“Think hard and produce a step-by-step plan before writing any code.”

Use Rich Inputs to Reduce Ambiguity

Images: UI screenshots, diagrams

URLs: Docs, specs, references

File paths: Explicitly name files to use

These inputs dramatically improve relevance and reduce wasted iterations.

Key Principles

Holistic Design: Treat instructions, knowledge, tools, and prompts as an interconnected system.

Iterative Refinement: Continuously test and adjust context and prompts based on outcomes.

User-Centric Focus: Design context around real workflows, not theoretical completeness.

Scalability: Support both small tasks and complex, multi-step work.

Maintainability: Build context structures that can evolve as requirements change.

Best Practices

Start Simple: Begin with minimal context and expand deliberately.

Measure Impact: Track relevance, task success, and user satisfaction.

Version Context: Keep context files under version control for traceability and rollback.

Integrate Feedback: Use human and production feedback to refine context continuously.

Keep Context Fresh

Context is a finite resource.

Clear context when switching tasks

Compact (summarize) context for long-running work

Avoid letting the context window grow unchecked

Fresh context improves focus and accuracy.

Create Custom Commands

Repetitive prompts waste time and introduce inconsistency.

Instead, define custom slash commands for common workflows (e.g., security review, performance analysis). Store them as markdown files (for example, in .claude/commands/) so they are reusable, consistent, and easy to evolve.

Start Small, Expand Deliberately

Resist the urge to create an exhaustive CLAUDE.md up front. Because it’s injected into context every time, keep it concise and high-signal. Break detailed guidance into separate markdown files and reference them selectively.

The goal is not more context—it’s the right context, activated by the right prompt.

References

Context engineering:

Spec Drive development:

Research Plan Implement:

Key principels and best practices:

-Sanjai Ganesh Jeenagiri